THE JOURNEY TO THE SILENT ASSASSIN—FROM AN ENCOUNTER WITH A SKULL...TO A TRIP TO VIETNAM

|

|

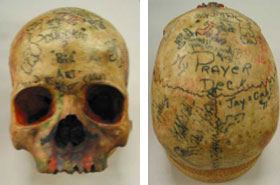

| Vietnamese Trophy Skull from the AFIP Photographed by George Loper |

On a trip to the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, I asked a question about an obscure scientific article I had stumbled across: “What are the Vietnamese Trophy Skulls?” My AFIP host pulled open a drawer and put a garishly graffiti-laden skull into my hands.

During the Vietnam War, some U.S. G.I.s collected skulls of enemy soldiers—turning them into ashtrays and candleholders. When the soldiers tried to bring them back through U.S. Customs, the skulls were confiscated and relegated to a drawer at the AFIP.

At that moment, I saw the potential for a fictional thriller. What if the contemporary Vietnamese government asked for the skulls to be returned, much as Native Americans asked for repatriation of the remains of the bones of their ancestors? In THE SILENT ASSASSIN, my protagonist, Dr. Alexandra (“Alex”) Blake, is preparing a skull for its return when she discovers evidence inside it of a thirty-year-old murder. Trailing the killer takes her from the bustling streets of modern Vietnam to the halls of power in contemporary D.C. Uncovering a plot against the President, Alex faces peril as she rushes to determine if the threat lies within the U.S. government—or if contemporary Vietnam is declaring war on the U.S.

![[photo]](images/lori_bunker.jpg) The journeys Alex makes in the book mirror my own journeys. I went to Vietnam to see what my character would encounter there. The trip was alternately haunting and enchanting. My first stop was the anti-American War Remnants museum that I describe in the prologue to THE SILENT ASSASSIN. I was traveling with a man who’d been drafted in 1969 to serve as a young infantryman in the Vietnam War. Our trip through the museum was incredibly moving. An entire room is devoted to photos of and by photographers—from the United States and around the world—who were killed while covering the war.

The journeys Alex makes in the book mirror my own journeys. I went to Vietnam to see what my character would encounter there. The trip was alternately haunting and enchanting. My first stop was the anti-American War Remnants museum that I describe in the prologue to THE SILENT ASSASSIN. I was traveling with a man who’d been drafted in 1969 to serve as a young infantryman in the Vietnam War. Our trip through the museum was incredibly moving. An entire room is devoted to photos of and by photographers—from the United States and around the world—who were killed while covering the war.

The next day, we visited the spot where my friend’s base camp had stood. We also descended into the Cu Chi Tunnels, not far from his camp. This immense system of 200 kilometers of underground tunnels—which included hospitals, a war room, dormitories, and weapons caches—was used by the North Vietnamese Army as a hiding place and a central operations center to plan attacks that took the lives of American and South Vietnamese soldiers.

The morning of our visit to Cu Chi my friend had entered the lobby of my hotel wearing a lapel pin in the shape of a bolt of lightning, with the insignia of his unit, the 25th Infantry Division (whose nickname was Tropic Lightning). He felt an urge to wear this small understated piece of metal to honor his fallen friends, but he also wondered what the impact would be if anyone recognized it. I, too, worried how the Vietnamese people we met would view his badge. A few minutes later, though, a Vietnamese gentleman who was to be our interpreter entered the lobby. He saluted my friend! Turns out he was a South Vietnamese soldier, whose own base camp was not far from my friend’s. Then, this 59-year-old Vietnamese man burst into songs in English, singing everything he remembered American soldiers singing and listening to during the war. The Animals’ We Gotta Get Out of This Place. Peter, Paul and Mary’s rendition of John Denver’s Leaving on a Jet Plane. As he sang, we could practically feel the sweat on young soldiers’ brows. That afternoon, in a dingy flea market that sold mainly used plumbing equipment, we saw a pile of American high school rings for sale, probably from men who had been killed. Viewing them, I was overwhelmed with a desire to send them back to the families of the dead men, just as my character, Dr. Alex Blake, is drawn into the struggle for the return of the remains of American soldiers.

The morning of our visit to Cu Chi my friend had entered the lobby of my hotel wearing a lapel pin in the shape of a bolt of lightning, with the insignia of his unit, the 25th Infantry Division (whose nickname was Tropic Lightning). He felt an urge to wear this small understated piece of metal to honor his fallen friends, but he also wondered what the impact would be if anyone recognized it. I, too, worried how the Vietnamese people we met would view his badge. A few minutes later, though, a Vietnamese gentleman who was to be our interpreter entered the lobby. He saluted my friend! Turns out he was a South Vietnamese soldier, whose own base camp was not far from my friend’s. Then, this 59-year-old Vietnamese man burst into songs in English, singing everything he remembered American soldiers singing and listening to during the war. The Animals’ We Gotta Get Out of This Place. Peter, Paul and Mary’s rendition of John Denver’s Leaving on a Jet Plane. As he sang, we could practically feel the sweat on young soldiers’ brows. That afternoon, in a dingy flea market that sold mainly used plumbing equipment, we saw a pile of American high school rings for sale, probably from men who had been killed. Viewing them, I was overwhelmed with a desire to send them back to the families of the dead men, just as my character, Dr. Alex Blake, is drawn into the struggle for the return of the remains of American soldiers.

![[photo]](images/lori_vietnam_office.jpg) Not all of my Vietnam research had an eye to the past. I thought about what Alex would want to see if she were visiting that country today. Two amazing scientists, Dr. Minh Tran and Vinh Nguyen, took me behind closed doors at the Institute for Tropical Biology in Vietnam, where I learned of their compelling efforts to use the healing powers of plants to design modern day drugs. Their work traces back to England in 1775, when Dr. William Withering discovered that digitalis in the foxglove plant could treat heart disease, a treatment still used today.

Not all of my Vietnam research had an eye to the past. I thought about what Alex would want to see if she were visiting that country today. Two amazing scientists, Dr. Minh Tran and Vinh Nguyen, took me behind closed doors at the Institute for Tropical Biology in Vietnam, where I learned of their compelling efforts to use the healing powers of plants to design modern day drugs. Their work traces back to England in 1775, when Dr. William Withering discovered that digitalis in the foxglove plant could treat heart disease, a treatment still used today.

In writing the book, I also learned a lot about how skulls—and other body parts—have long been collected by soldiers as souvenirs of war. In Kyoto, Japan, the Korean Ear Mound is a 500-year-old pile of thousands of ears that Samurai warriors cut off their enemies. The Samurai generals got a bonus for each soldier they killed in Korea. At first they sent back heads, but when the ships got too crowded, they started dispatching just the ears. Recently, a group of Korean monks placed fifty Korean flags on top of the mound and began to negotiate for a return of the ears, at least spiritually, to Korea. In my novel THE SILENT ASSASSIN, that real life incident is what provokes the Vietnamese government to ask for the Vietnam Trophy skulls back.

Links:

For a wonderful essay on Trophy Skulls, see George Loper’s blog, http://george.loper.org/trends/2002/Mar/65.html

The best book by an American on contemporary Vietnam is David Lamb’s Vietnam Now: A Reporter Returns.

For a fabulously-written book about Vietnam during the war years, read Frances Fitzgerald’s Fire in the Lake: The Vietnamese and the Americans in Vietnam, which won both a Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award.

More Vietnam photos:

Click on an image to enlarge it.

Cao Dai Temple |

|

|

|

|

|

|

My guides in Vietnam |

|

Opera House in Ho Chi Minh City |

Traffic in Ho Chi Minh City |

|

Lori in front of Blue Ginger, where one of the characters eats in THE SILENT ASSASSIN. |

|

|

All content © 2006-08 by Lori Andrews.

loriandrews.com